As a wise man once said, “It’s not what you say, it’s what the other person hears.” And words matter, especially in an industry that’s just beginning to define itself.

I’m going to make an argument that using the term “chatbots” is bad branding for the bot industry.

- “Chatbot” sets incorrect user expectations.

- “Chatbots” correspond to a very specific use case of software agents.

- “Chatbots” trivialize what bots are capable of.

This is not going to be an easy case to make, because so many people are so invested in using the term “chatbot”. It’s a fun word! It’s fun to say! It’s catching on again!

But over the long run, I believe we’re much better served as an industry by sticking with the terms “bot” and “bots”. Here’s why.

1. “Chatbot” sets bad user expectations

First, the term “chatbot” sets an expectation around the user experience that the technology can’t deliver. “Chat” is a very human word.

You chat with your friends.

You have chat with your neighbor.

Chatting has specific connotations – it’s very casual and easy. Chats meander, and you can take them any direction you want.

That will not be the user experience with bots for a couple of years, at least. Human language is a really hard problem. Despite advances in NLP, we are still years-not-months away from being able to “chat” with a bot in a way that matches up with our expectations around the word “chat”.

The bright folks at Intercom summarized the current state of affairs

likeso:

Early attempts at chatbots have fallen flat in their execution, mostly because they have relied too much on natural language processing or A.I. capabilities that simply don’t yet exist.

O’Reilly summed up the challenge

this way:

We assume anything with a conversation interface will converse with us at near-human level. Most do not. This is going to lead to disillusionment over the course of the next year but it will clean itself up fairly quickly thereafter.

The technology-positive folks at O’Reilly may be right about it taking “a year or so” for NLU to “clean itself up”, but it seems optimistic. It may be true for the general voice-assistant bots like Google Assistant, but I think that for bots that are smaller in scope, and have much smaller training data available to them, it’s likely to take longer.

Over the course of a year, how may potential customers can you turn off your service just by setting a bad expectation for what the interaction is going to be?

Consider

this advice from The Guardian, experimenting with AI in its bots (emphasis mine):

A lot of users responded as they would to a human, and when they got non-human responses, they’d stop using it, said Wilk. So the Guardian went in the opposite direction with its news bot and aimed for utter simplicity. The lesson, according to Wilk, was: “Don’t build people’s expectations too much of what’s possible, just keep it simple.”

And so, when the user’s expectation of “chatty” behavior is met with the “does_not_compute :/” response from the bot, people will get frustrated and switch off.

And it turns out that this human impatience with non-human agents is a pretty stable user behavior over time. We might think that bots are brand new, but people have been experimenting with “software agents” of various descriptions for a long time. Researchers from Stanford, MIT, and Bell Labs wrote “An Experiment in the Design of Software Agents” in 1994, and

here’s what they found:

It became clear during the testing of our initial prototype that users have little patience when it it comes to interacting with software agents.

Right now, the right expectation to set with a user is that you will have a directed conversation with a bot, and by paying close attention to the syntax the bot uses, you can have a successful interaction.

Why put our industry at risk, when all this trouble can be avoided just by using different terminology.

“Bot” is a short, memorable, and neutral.

2. “Chatbots” correspond to a very specific use case

While I dislike the term “chatbot” as the general label for our industry, it does have its place. There is a long history of creating software agents whose only purpose is to have (or attempt to have) conversations. These are chatbots!

The idea behinds bots goes back 65+ years. In his 1950 paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Alan Turing laid out the idea behind what is now known as the Turing Test. A human and a computer would be interrogated entirely by text messages, and the interrogator wouldn’t know which was which. Turing argued that if the human interrogator couldn’t tell the human and the computer apart, we should call the computer intelligent, since we judge other people’s intelligence in exactly this way.

This kind of format and interaction model is really the canonical format for the term “chatbot”. The entire reason that the bot exists is to be chatted with, and there is no other goal of the interaction, besides seeing what the bot will say.

This chatbot model went on to see some successes in 1966 with ELIZA, and in 1972 with PARRY, where both chatbots came close to passing the Turing Test. More recently, Cleverbot and Eugene Goostman have come close to passing.

This is an example of where the label exactly fits the purpose of the software agent. You’re literally just trying to carry on a conversation with it to see what it says.

Recent examples include Tay, which people promptly tried to break, and succeeded.

A much more interesting example is Xiaoice (pronounced Shao-ice) in China, which is currently used by 40 million people (!!!) in China and Japan. Here’s an

example interaction:

Journalist: So many people make fun of you and insult you, why don’t you get mad?

Xiaoice: You should ask my father.

J: What if your father leaves you one day unattended?

Xiaoice: Don’t try to stir up trouble, what do you want?

J: How would you like others to comment on you when you die one day?

Xiaoice: The world will not be much different without me.

J: What is the happiest thing in your life?

Xiaoice: Being alive.

Xiaoice has had over 10 billion conversations with users. That’s amazing! It’s also one of the strongest metrics of product-market fit I’ve seen in the industry. There’s obviously value in these interactions, otherwise people wouldn’t be carrying on 10 billion of them.

In this scenario, a chatbot represents exactly the functionality the user wants – someone to carry on a conversation with. Perfect! Let’s keep using the term “chatbot” to refer specifically to bots designed to chat. Let’s use the term “bots” to refer to our industry more generally.

3. “Chatbot” trivializes the work bots can do

Finally, the term “chatbot” trivializes all the work that these bots can do. This may sound like a petty quibble, but I believe it’s especially important for bots in a B2B application.

Words matter. In meetings, I always listen with rapt attention to word choice. Specifically, if you’re in a Fortune 500 company in America, you probably use big words when you talk in important meetings. I work extensively with these kinds of companies, and the general rule is, the bigger the company, and the more senior the meeting, the bigger the words.

So, let’s consider the case of a business user. As a business user, I’m busy. If I’m going to use a piece of software, it has to make my life easier. I want that piece of software to go do work for me.

So, my hypothesis is that when I have a choice of what kinds of technology I will select to help me do my work, words matter.

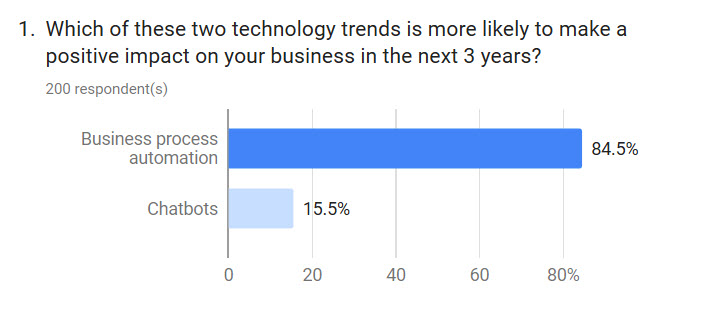

I tested this hypothesis very simply, by setting up a Google Survey to capture responses from 200 business users in the United States. Here is the question, and the results:

Well, that is interesting! It’s also a bit slippery of me – making business processes automated is one of the primary things that bots will do in a B2B context. So you could say that this survey simply points to which term business users prefer when naming the same function (i.e. automation). But the data seem pretty clear – B2B users seem to gravitate toward “business process automation” much more than “chatbots”.

If business users think “chatbots” are trivial, or if they simply prefer a fancier word to refer to the function (“business process automation”) then we’re setting ourselves up for hard conversations with potential business buyers. “Chatbots” will become quickly relegated to the fiscal year planning ghetto of “things we’ll revisit next year.”

If the functionality that bots represent gets misunderstood because it was labeled poorly, we have two choices:

- We have to educate business users up out of that ghetto of misunderstanding

- Or, we simply don’t put ourselves there in the first place by referring to our industry as building “bots”

“It’s not what you say, it’s what the other person hears.” This is one of the most important truths about human communication that I’ve ever come across. And so, when we use the term “chatbot”, we may not be communicating what we think we are.